May 9, 2020

Clay court tennis and Andy Murray had always been a peculiar mix. During his teenage years, he swapped the indoor tennis centre at Stirling University in Scotland for the Sanchez-Casal Academy near Barcelona. The hours of practice he could do on the clay was thought to pay dividends on the surface once his career started, but it did not exactly turn out that way.

Between 2008 and 2013, he reached the semi-finals of the French Open once and the quarter-final stage on a further two occasions. While this was a relatively impressive record, it did not compare to Murray’s record at the other majors because he had reached seven major finals by the end of 2013. And he was still yet to win a clay court singles title in his career.

But from 2015 till the end of the 2017 clay court season, during which period he also became the world number one, Murray proved himself to be one of the best clay court players in the world. He won three clay court titles between 2015 and 2016, including victories in two Masters 1000 tournaments, and beat Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic on the surface.

As this week marks five years since Murray won his first Masters 1000 title on clay, I decided to look at what are some of key changes the three-time Grand Slam champion made to improve his results on the surface. Was it adjusting to the longer rallies more consistently? Was it just taking his strengths and implementing them on the surface? I had a look at some of the data to find out.

For this analysis, I have looked at Murray’s clay court season results from the period of 2010 till 2014, which is when he established himself as a true part of the “Big Four”. Then, I looked at the period from 2015 to 2017, where he took his game to another level and reached a clay court prowess which was second to none. I looked at specific match data for the singles matches Murray played on the surface to see if there were any changes he made.

But before looking at the match data, there is one very important aspect to consider with Murray’s career, not just his clay court tennis. Having back surgery in the back end of the 2013 season because of the unrelenting pain he felt was undoubtedly the biggest factor for his difficult 2014 season. Losing to Roger Federer 6-0 6-1 in the final group match of the ATP Finals at the O2 Arena was probably the last straw for Murray. He knew that before competing again, he would need to get his back in top shape. His back would trouble him again officially in 2017, it probably always did, but for those two and a half years, Murray was in the best physical shape of his career. And it told on the surface of clay the most.

If we consider the strengths of Murray when he is playing his best, a few things stand out. An immensely strong first serve which can often be hit north of 130 miles per hour. Exceptional defensive skills were always his trademark, but he had a very aggressive forehand too. The one two punch he would implement off the back of a strong serve would just run through many opponents. Yet in the early part of the 2010s, it seemed as though Murray did not play to his strengths on clay.

Between 2010 and 2014, Murray would average 56.9% of his first serves in play for the clay court matches he played. This is despite his average across those years on all surfaces being close to 60%. It also added to his ace percentage on the surface. After averaging close to 10% aces in his clay court matches during the 2010 season, his numbers of aces dwindled for the next few years. The doubts Murray had in his movement on the surface seemed to be curtailing him of using his key skills. The surface he was playing on also probably played a role.

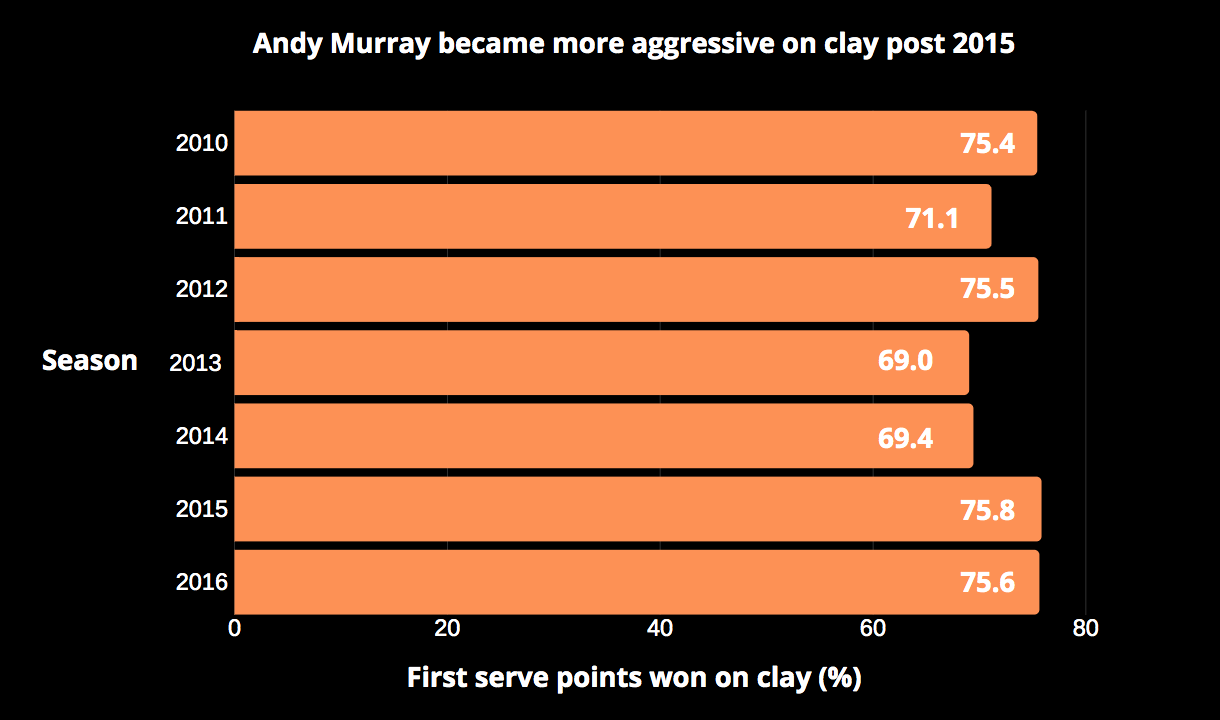

Playing on clay naturally brings about thoughts of the grind and long rallies. While this would seem to play into Murray’s hands, it should be remembered that when Murray was at his absolute peak, he was consistently attacking and keeping the rallies short. He would still win a lot of exceptionally long rallies, but he made sure to win the shorter rallies too. That aggressiveness showed in his serving statistics for the 2015 and 2016 seasons. He averaged 7.7% aces in his clay court matches and he won 76% of his first serve points. With his movement feeling much better, Murray was finally able to show his prowess on the serve on clay. But what about his return game?

In this modern generation, it should not come as a surprise to tennis fans if someone says Novak Djokovic and Murray have been the best returners in the sport. Time and again, both players have been able to get balls back in play from what were seemingly un-returnable serves. Yet if we look at the figures for Murray between 2015 and 2017, where he made two semi-finals and a final at Roland Garros, his return points won were actually down.

From 2010 to 2012, Murray won an average of 43.9% return points that he played in his clay court matches. In 2011, he won a very impressive 42% of the first serve points he returned on the surface. Fast forward to the 2015 and 2016 season, Murray won an average of 36% of points on his opponent’s first serve. While this is still a formidable number, the drop compared to the earlier years suggests that Murray was looking to implement his all court game more than adapting to clay.

Rather than learning the tricks of the trade on the slow surface, Murray seemed to put all his focus on developing a game style that would work on any surface. He would approach the net more and more, try and be more aggressive and rely less on winning unbelievable winners from far behind the court. This strategy yielded great results as between 2015 and 2016, he compiled an 18-3 record on the surface which was the best in the world. Even better than Nadal, the greatest clay courter of all time, and Djokovic.

He was beaten by Djokovic in those two years at the French Open as he resorted to the old tactics at times, while the Serbian took advantage. But Murray had proven that with his improved health, he was a formidable clay court player without adapting to the surface. As Nadal said in Monte Carlo in 2016: “Andy is a great player on any surface. He is a great player on clay.” That stretch seemed like Murray finally believed that himself too on clay.