January 10, 2020

Batting in the fourth innings of a test match. It is quite possibly the most difficult thing to do in the longest form of the game and in the last week, we have seen two examples in different parts of the world.

In Sydney, New Zealand ended a troubled tour with a fourth innings total of just 136, chasing a target of 416. Australia dominated with the bowling attack, like they had done throughout the series, and got all ten wickets required in just 47.5 overs.

In Cape Town over one and a half days, South Africa showed incredible resolve to take the match within nine overs of ending in a draw as they chased 438. But, with some magic from the world’s best all round cricketer in Ben Stokes, England got the ten wickets they needed to draw the series in a mammoth 137.4 overs.

Chasing similar sized targets, New Zealand and South Africa showed differing approaches to batting last in a test match. The Kiwis had five batsmen with a strike rate above 50, whereas the Proteas had no batsmen with a strike rate of more than 47.

Of course these two teams were up against high quality bowling attacks and were always going to be up against even getting a draw, with so much time left in their respective matches. But the rarity of successful chases or digging out a draw in test match cricket is increasing. What does it take to win or draw nowadays?

Any chase in the fourth innings below 150 is one where the batting team will consider themselves as slight favourites, even if the pitch is a minefield. But above that figure, the bowling team will be confident that even if they cannot pull off the win, they can at least cause the opposition problems.

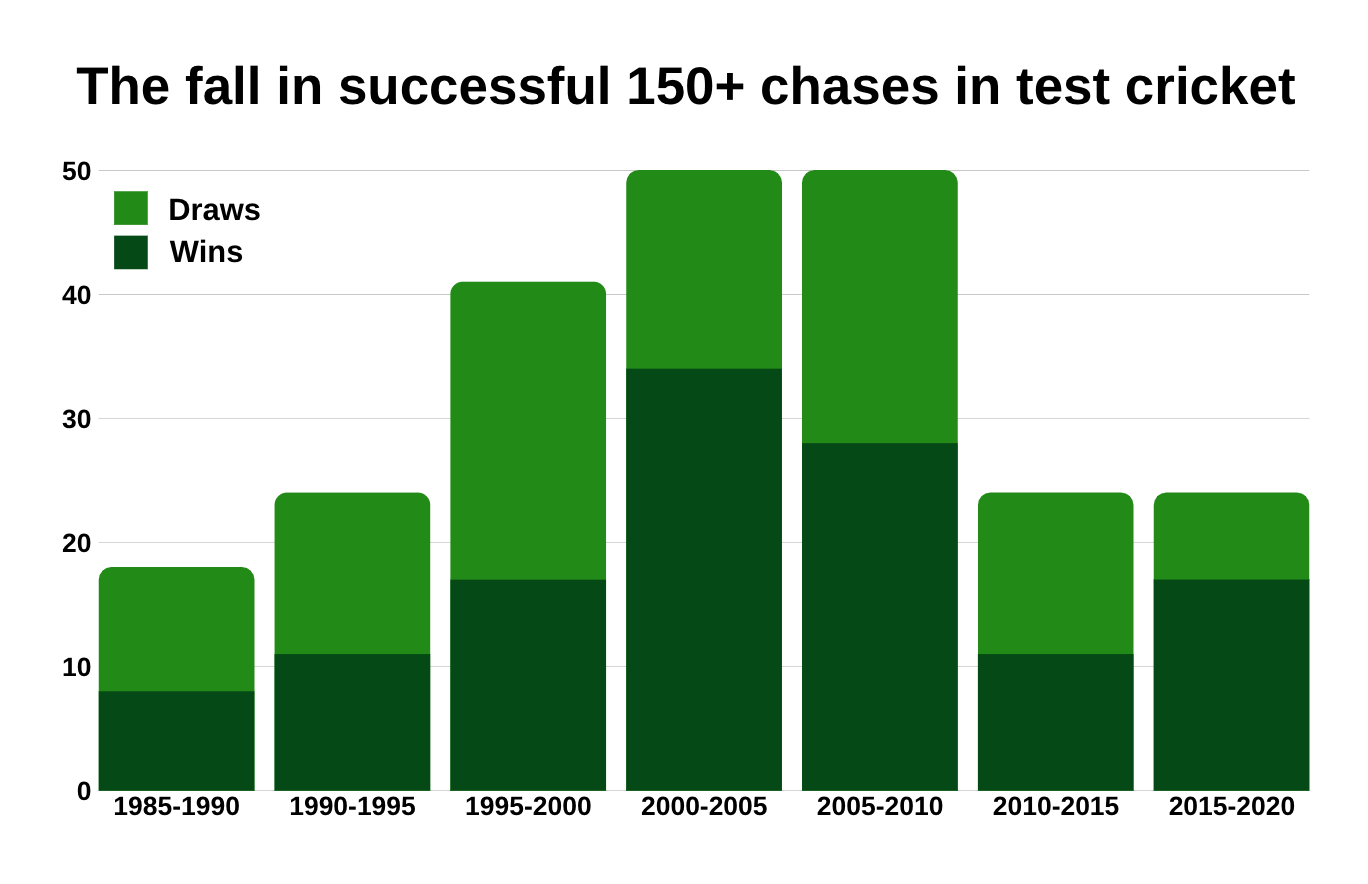

Since 1 January 2015, there have been 17 successful chases of more than 150 in the fourth innings of a test match, while there have been seven draws. This is the lowest it has been for a five year period since between 1985 to 1990, when there were eight successful chases and ten draws.

Between 1985 and now, the most successful period for chases of 150 or more in test match cricket was between 2000 and 2005. There were 34 victories and 16 draws for the team batting last.

Last year saw two incredible chases at Durban and Headingley by Sri Lanka and England when they chased totals in excess of 300 with just one wicket remaining. But the large majority of chases in the last five years have proved to be too much for the batting team.

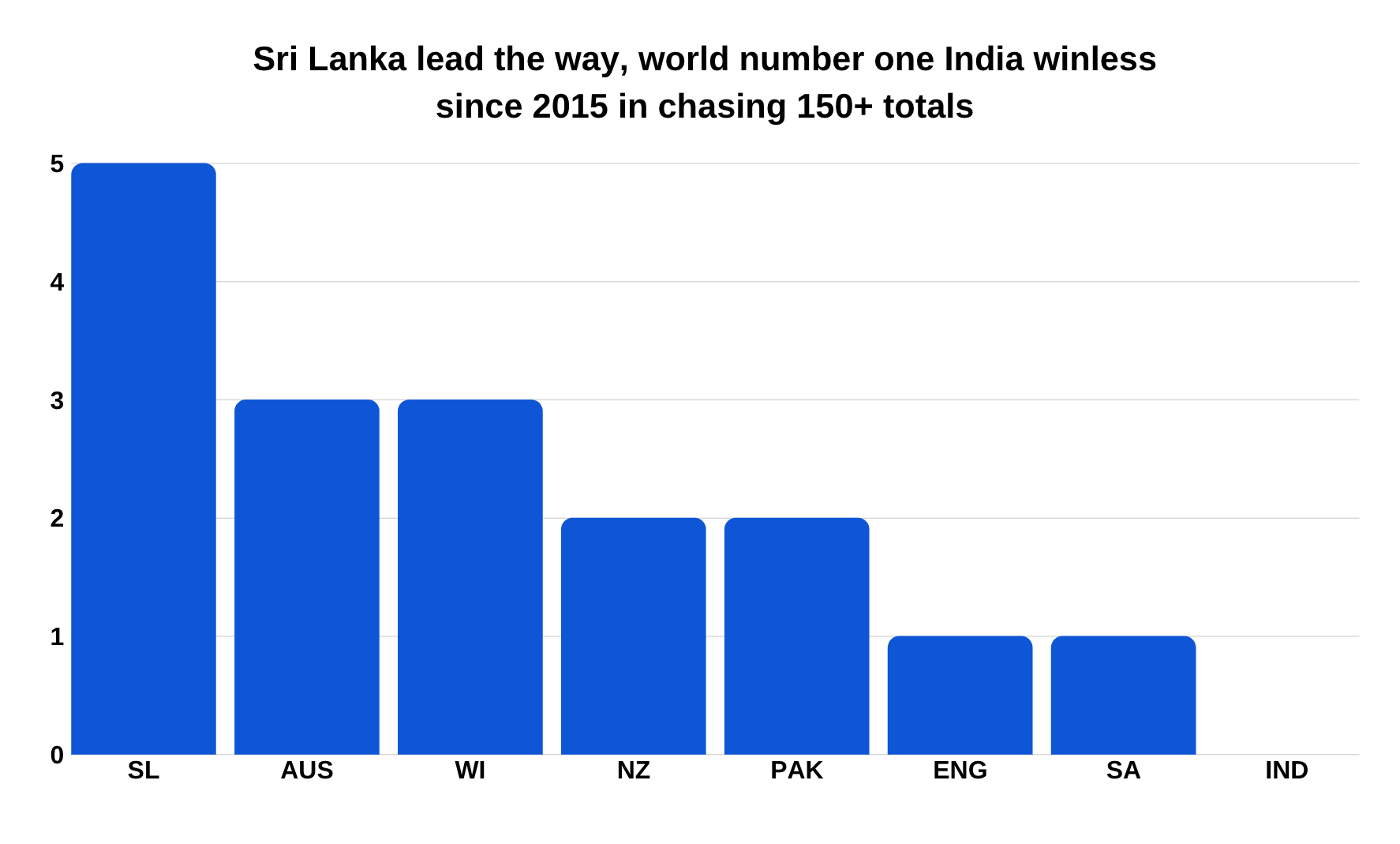

Surprisingly, of the top eight test match sides in the men’s rankings, number one ranked India are the only side to not record a victory in a chase where they have had to make more than 150 in the last five years. They have had eight losses and only two draws since the start of 2015, losing their last seven such chases.

In fact the top five in the test match rankings, India, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and England account for only seven chasing victories above 150 in the last five years. The lower ranked trio of Sri Lanka, Pakistan and West Indies have accounted for ten such victories, with Sri Lanka impressively winning five chases.

When looking at why this is the case, conditions cannot be pointed to as a significant factor, or the only factor, because teams like Sri Lanka won in South Africa and West Indies won at Headingley in 2017. There is no specific trend in terms of certain conditions being more conducive to chasing victories but there are some patterns in the ways teams win when batting last in a test match.

The importance of a substantial opening partnership is often spoken about when batting in test match cricket, but of all the victories in the last five years for targets of 150 or more, only two matches saw the opening partnership be the highest of the fourth innings.

In seven of the 17 victories mentioned in the last five years, the third wicket partnership was the highest and often batsmen number five, six and seven have played crucial roles.

For example, the highest successful chase in the last five years was by Sri Lanka against Zimbabwe at Colombo in 2017. You may scoff at the opposition but a chase of 388 is still formidable. And when the first three wickets fell with 258 still required, Zimbabwe were a real chance of winning. But the trio of Angelo Matthews, Niroshan Dickwella and Asela Gunaratne contributed 186 runs while batting at five, six and seven.

Another interesting example is that of Australia’s match against New Zealand at Adelaide in 2015. It was the first ever day night test match and Australia won a thriller, chasing 187 with only three wickets remaining. The first three partnerships only contributed 66 runs, but batsmen five, six and seven scored 87 runs between them. Shaun Marsh, batting at five, scored 49 which was the highest in the innings.

However, this does not mean that the top three or four batsmen do not have a role to play. Often in matches now, there is a lot of time left when teams come out to bat in the fourth innings, such as what we saw in Sydney and Cape Town earlier this week.

Along with taking the game forward, the top order has a responsibility to make bowlers work extremely hard for their wickets, and make them bowl as many overs as they can. For all the fantasy around Stokes’ three off 73 balls in the opening part of his Headingley heroics in the Ashes, Joe Denly and Joe Root made sure the Australians were already feeling the strain. The top four batsmen in that innings faced 399 balls in total during their time at the crease in the innings.

When Pakistan chased a seemingly improbable 376 against Sri Lanka at Pallekele in 2015, Shan Masood and Younis Khan faced an astonishing 504 deliveries between them while batting in the top four. They did score at a decent rate of 3.7 runs per over but it also shows the value in the top order taking time to blunt deliveries and making it easier for the middle and lower order.

This is the case even for all time record chases or attempts in which the team batting last earned a draw. Since 2000, of the top ten chases that have resulted in victories or draws in test cricket, none of the fourth innings totals saw the opening partnership be the biggest of the innings.

For example, South Africa were set a target of 458 by India in December 2013, and incredibly got to a stage where they needed 16 runs to win off the final over. Dale Steyn’s final ball six could not get his side over the line but their score of 450/7 is the highest score in a chase that has ended in either a victory or draw in this century.

In Johannesburg over those two days, the highest partnership for the home side in that innings contributed 205 runs. That was the fifth wicket partnership between AB De Villiers and Faf du Plessis. While those two faced 477 deliveries and were undoubtedly the crucial figures, the importance of Alviro Petersen and captain Graeme Smith’s opening partnership cannot be overstated.

Petersen faced 162 deliveries for his score of 76 and even though Smith did not make a half century, him facing 73 deliveries meant that India were already feeling the strain by the time the opening wicket fell.

So what does all this analysis show? It shows that chasing in the fourth innings successfully is getting rarer by the minute (not all that surprising), but the key to chasing could in fact be with the middle and lower order rather than giving the responsibility all to the top order.